The illusion of a trillion trees

By Alexandra Heal in London APRIL 12 2023

© Mapbox © OpenStreetMap Improve this map © Maxar

When the billionaire Salesforce chief executive, Marc Benioff, appeared on the sidelines of the COP26 climate summit in November 2021 he was jubilant.

“This is a huge moment where world leaders, philanthropists and CEOs all came together around reforestation,” he said.

More than 100 countries had just pledged to spend $19bn of public and private money to reverse forest loss. “We have lost 3tn trees on our planet,” Benioff said, punctuating his words with a clap.“We need to plant a trillion trees.” This amount, he added, would absorb 200 gigatonnes of carbon — the equivalent of two-thirds of existing human-made emissions.

His glee seemed sincere. But when a journalist asked how he would measure what was actually being done, his answer offered no clarity. He simply replied that every chief executive must go net zero, as Salesforce had, and called for “an ecopreneur revolution”.

Benioff’s vision of fighting climate change with saplings is one of three “trillion-tree” campaigns launched by business leaders and charities in the past decade, alongside more than a hundred government planting pledges. The movement has gathered momentum so quickly there is now a global seed shortage.

Tallying exactly how many trees or how much land has been promised is impossible because the campaigns are all unclear about how their individual targets overlap with each other. A recent report said governments were separately aiming to plant and restore an area almost four times the size of India.

India’s climate pledge involves changing the use of nearly two-thirds of its land

Per cent of territory to change use or be restored under nature-based solutions in climate pledges

The Land Gap Report, 2022

Their intentions are commendable: draw down carbon, nourish biodiversity and improve livelihoods by returning trees to planet Earth. But the simple idea is now rubbing against a complex reality, as some scientists raise myriad concerns — from a dearth of free land to the unreliability of new trees when it comes to carbon storage.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says protecting and restoring the world’s forests is critical for limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, but many argue political and business leaders are focusing too much on “restoring” rather than “protecting”, and latching on to methods they hope will offset emissions rather than prevent them.

At least a third of the corporations promising to plant trees under Benioff’s 1t.org campaign are doing so to offset emissions, according to a Financial Times analysis of 73 pledge documents. The 46 planting pledges so far amount to at least 3bn new trees.

“It’s greenwashing,” says Kate Dooley, a lecturer specialising in carbon accounting at Melbourne university. “Corporations are greenwashing us when they say they will achieve net zero if that is relying on removing carbon through tree planting.”

Planting trees is more complicated than it sounds. Ecosystems must be restored to avoid biodiversity collapse, experts say, but “on the right land and in the right way”. Multiple projects so far have failed to benefit local people, others have created monoculture commercial plantations that are poor homes for wildlife, and a lack of continuing care means many saplings simply die.

Twenty-four of the 1t.org companies claim to have already planted nearly 300mn trees, some as far back as 2004, but only two projects disclose in their pledge documents how many survived.

Jack Hurd, executive committee member of the World Economic Forum, which runs 1t.org, says companies can only pledge with 1t.org if they, “at the minimum, have a credible, public net zero goal before or by 2050”. He says the campaign is helping companies to better monitor their projects, including survival rates.

The People

Limited land

The tree-planting movement's touch paper was an unlikely partnership between the Kenyan founder of the Green Belt Movement, Wangari Maathai, and a German schoolboy. In 2006 Maathai launched a billion-tree campaign backed by the UN, inspiring Felix Finkbeiner, then nine years old, to call in a school presentation for children to plant 1mn trees in every country.

Their positive message was infectious. Maathai died in 2011 but by then Finkbeiner's nascent organisation, Plant-for-the-Planet, claimed to have planted a million trees. Soon his original goal ballooned into the Trillion Tree Campaign.

As excitement snowballed, so did the movement. Since 2011, the German government’s Bonn Challenge has encouraged national governments to restore degraded lands equivalent to the size of India by 2030. In 2016, a coalition of wildlife NGOs jointly launched their own Trillion Trees campaign initiative and, four years later, Benioff’s effort joined the pack.

A Plant-for-the-Planet worker collects seeds from a tree near Constitución in Campeche, Mexico © Plant-for-the-Planet

The Plant-for-the-Planet team place saplings in a clearing near Constitución in Campeche, Mexico © Plant-for-the-Planet

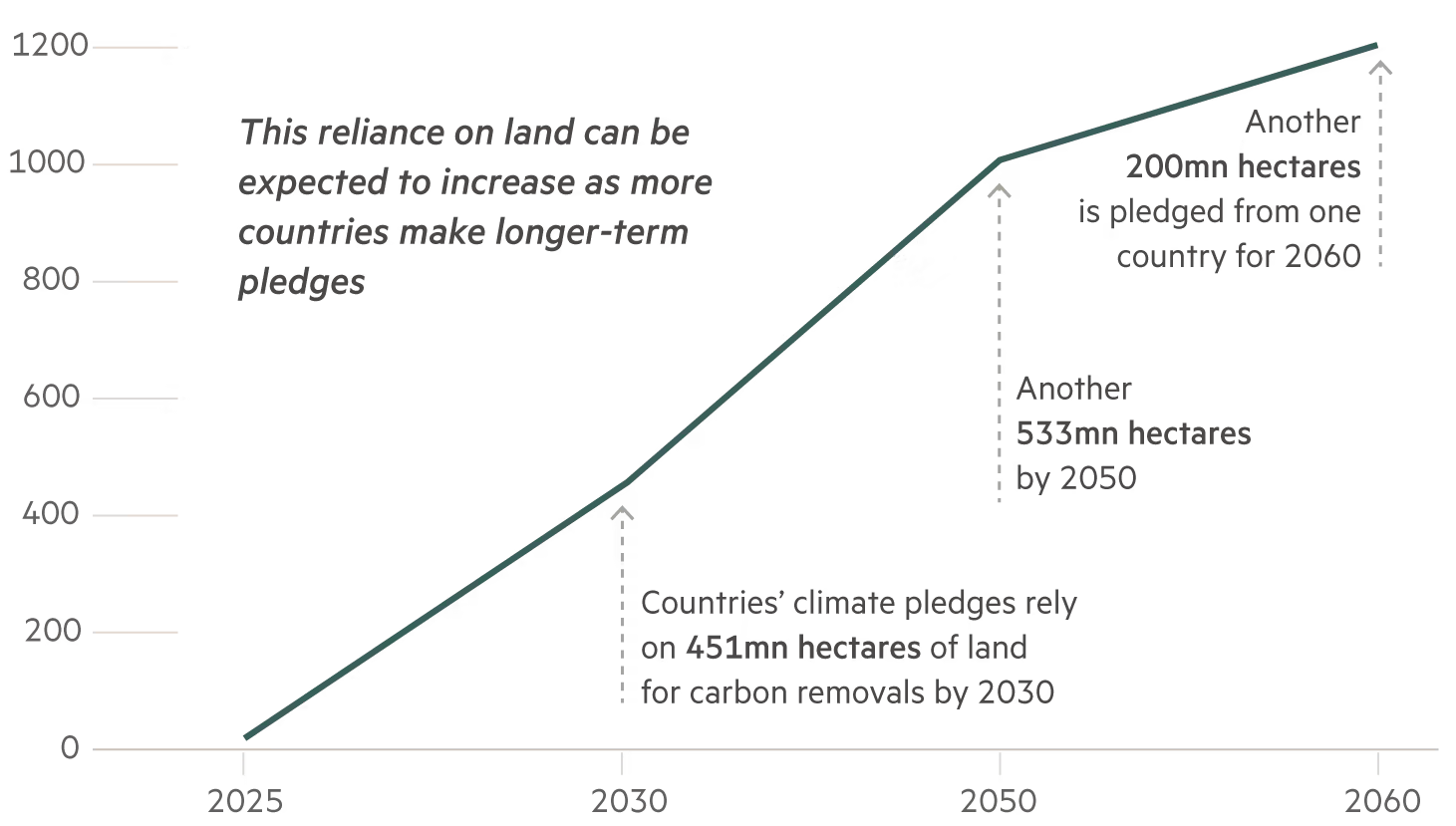

No organisation is centrally tracking the amount of land earmarked for the cause and it is unclear to what extent the trillion-tree campaigns overlap with the often vague afforestation and land restoration pledges in governments’ Paris Agreement net zero plans. But last year Dooley, of Melbourne university, translated their promises into land area and found they amounted to planting and restoring nearly 1.2bn hectares.

This equals almost a tenth of global land, excluding ice and barren rock, or about a quarter of total agricultural land. Dooley and others argue there is simply not enough space for the ambitions to be met. For 633mn of the 1.2bn hectares — or nearly twice the size of India — the plans would involve changing land use, such as adding trees to areas not currently forested.

Government climate pledges equate to planting and restoring 1.2bn hectares by 2060

Hectares (mn)

The Land Gap Report, 2022

Much of this land will be used for agriculture, Dooley says, and puts communities at risk of displacement. “There are no unused, abandoned or large tracts of land that people aren’t using out there,” she says. Decades-old schemes in south-western China that converted cropland to tree plantations, known as afforestation, led to felling in domestic native forests.

The Irish government’s net zero strategy aims to afforest an area larger than the UK city of Leicester each year. The document and its draft forestry strategy are unclear on how this can be done without affecting food production. The Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine says most of the 8,000 hectares a year would be met by farmers voluntarily planting their own land.

Elsewhere, some criticise the tree planting movement for targeting land in the global south, where trees grow faster and land is cheaper. One scenario in a 2020 study mapping global land with restoration potential was later found to prioritise substantial proportions of agricultural land in tropical countries but not in temperate ones. It classified more than 96 per cent of estimated agricultural land in the Philippines and Equatorial Guinea as a top restoration priority.

Those in the trillion-tree movement cite the study to galvanise support, alongside a second report that claimed 900mn hectares of land globally could support new trees, but some scientists argue such maps lack local land use knowledge.

Half of global land actively managed by humans is devoted to livestock grazing

Million sq km

At least 70% of global land area is impacted by human use

The Land Gap Report, 2022; IPCC 2019

John Lotspeich, executive director of Trillion Trees — a joint project of the Wildlife Conservation Society, World Wildlife Fund and BirdLife International — says his coalition is only targeting land it is sure is unused.

Finkbeiner, of Plant-for-the-Planet, similarly says the displacement risk is “widely discussed”. He adds that the global maps are not intended to dictate specific planting locations and that most projects in his campaign are instigated bottom-up by communities. “We do ask and ensure projects have thought about [displacement] and have some measures in place, but it’s hard to prescribe specific rules and standards to avoid it,” he says.

Finkbeiner points out the world has passed peak agricultural land use and loses on average4.7mn hectares of forest each year. “I understand that when you're looking at all of these pledges, you can be like, ‘This stuff doesn't add up, we're going to run out of space,’” he says. “But we're nowhere near running out of degraded sites that we could restore.”

Halving consumption of animal products would free up 1.55bn hectares of agricultural land, according to a 2018 study, but few governments actively encourage this.

What happens to the trees

Even if space were infinite, planting a tree and expecting it to permanently store carbon is unrealistic. This is primarily because many will be harvested in 20 or 30 years, says Simon Lewis, professor of global change science at University College London and the University of Leeds.

He says much of the tree mass ends up in temporary products such as construction chipboard or toilet roll. The carbon in these products then returns to the atmosphere when they are landfilled or incinerated.

Analysis carried out by Lewis in 2019 found nearly half the land pledged for “restoration” under the Bonn Challenge was earmarked for commercial plantations, many timber. Many Paris Agreement plans, including the UK’s and Ireland’s, also heavily feature timber.

The Irish government does not specify how much of its annual planting target will be divided between timber and native woodland.

Campaigners argue the policy is going to put farmers in direct competition with timber producers.

Brian Smyth, a campaigner in north-western County Leitrim, says decades of timber industry expansion in the area have already left many homes and villages surrounded by dark, impenetrable fortresses of sitka spruce.

“We’ve seen farm after farm now being bought up,” he says.

He suggests 30 per cent of land available for planting in the county is already covered in timber plantations.

1990

10 km

© OpenStreetMap

A local farmer recently contacted him because his siblings were selling the family’s farmland after their father died. “He attempted to buy the land but the price was beyond him,” says Smyth. “It’s gone to a commercial forestry operator who’s going to plant it all.”

The local farmland is “diverse pasture with small enclosed fields and vibrant hedgerows”, Smyth says, cheaper than the prime dairy and crop land elsewhere in Ireland. “We’re turning the most valuable land for biodiversity into monoculture plantations. It’s damaging.”

Still, timber is a renewable resource that the Irish government argues can replace carbon-intensive traditional housebuilding materials. The agriculture department says farmers are a key focus in its plans and it will pay them more than other landowners to plant trees, with a premium for native species.

Whatever the species, evidence from around the world suggests many saplings are not surviving. A recent study found nearly half of those in 170 Asian reforestation projects died within five years. The Ethiopian government generated mass publicity with its claim to haveplanted 20bn trees in 2022, but experts say the data on how many survived is unreliable. West Norfolk council in England claimed to have planted 6,000 trees last May, but when a sample of these was checked in August, 90 per cent had already died. The council blamed unusually hot and dry weather, but one campaigner believes they were not properly looked after.

Almost all of the 1t.org pledges mention monitoring of the saplings, but many do not offer methods or timescales.

“Rather than saying, ‘We're planting a trillion trees’, I would like to see people saying, ‘We want this many trees that are alive in 10 years.’ Even five years would be an improvement upon what's being done right now,” says Karen Holl, restoration ecologist at University of California, Santa Cruz.

For the trees that do reach maturity, experts say political and business leaders are overhyping their ability to absorb today’s and tomorrow’s copious emissions. Trees “are just placeholders”, argues James Dyke, associate professor of earth systems science at Exeter university, as leaders seek to pass the decarbonisation burden on to their successors.

Natural climate solutions can only contribute to a small portion of total required net emissions reductions

Global carbon emissions (billions of metric tonnes of CO₂ per year)

How to read this chart: The grey shading represents an estimate of how much natural climate solutions - such as forest conservation, restoration and improved farming practices - can account for the needed net emissions reduction to keep warming to below 2C. This estimate relies on reforesting 30% of grazing lands in previously forested areas by reducing meat consumption and increasing the number of animals per hectare

Grissom, B.W. et al, Natural Climate Solutions, PNAS 2017

The IPCC does recommend nature-based solutions for removing existing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, but alongside massive cuts to global emissions, which have been relatively flat since 2015. If this trend continues, global warming is likely to hit 1.5C in nine years, while trees take several decades to start removing significant carbon from the atmosphere. They may also be cut down or killed off by climate change-induced fires and droughts.

Those running the trillion-tree campaigns agree tree planting is not an alternative to slashing emissions. “We cannot plant our way out of this problem,” says Hurd of WEF. “Reforestation is not a magic solution nor is it a substitute for reducing fossil fuel use.”

The people

Scientists and trillion-tree campaigners are united in saying that protecting existing forests is the most important nature-based solution for limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5C. But sensitively restoring ecosystems in appropriate places is crucial for slowing biodiversity collapse, they say, and must be done with urgency.

“Climate change is a massive threat to society and must be addressed with emissions cuts. Biodiversity loss is an equally big threat to humanity,” says Thomas Crowther, ecologist at ETH Zürich, a public research university. “It's not like we can do one and then we'll fix the other.”

Crowther co-authored a paper claiming 900mn hectares could support “additional” tree cover. This estimate was later disputed, but Crowther says it could be achieved by communities adopting natural solutions to improve their livelihoods, for example growing coffee under taller tree canopies that attract water and nutrients. This prevents the “delineation of land” between restoration and farming, he says.

Dooley, of Melbourne university, similarly defines restoration as adding trees to farmland, known as agroforestry, or to existing forests that have been cleared then deserted. Her report said just under half the land pledged in government net zero plans appeared to be earmarked for this, a more “promising” approach than land use change.

The main goal of restoration should be protecting biodiversity, with any carbon absorption a “happy side-effect”, says Bonnie Waring, senior climate change lecturer at Imperial College London. But this would involve a rethink of many efforts, because planting methods with a goal of quick carbon absorption are often at odds with those best for biodiversity.

Trees can’t do all the things many projects are asking of them, says Meredith Martin, forest ecologist at North Carolina State University. She found in a study of 174 tree planting organisations that many touted the climate, biodiversity and economic development credentials of each project, rather than focusing on one or two.

The economic development benefit is often especially ill-thought-out. A series of studies recently found five decades of government-funded afforestation in the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh had little positive impact.

The state forest department in Himachal Pradesh, India, has long promoted monoculture pine plantations in the Kangra District © Harry Fischer

Tree composition shifted away from the broadleaf species preferred by local people’s livestock. Some of the planting disrupted pastoralists’ migratory routes. In a survey of 2,400 households living near the new plantations, only 9 per cent said they had high or medium dependence on them. Less than one per cent of the $5.6mn spent on tree planting over four years went to community-managed lands.

“Use is low and the funding going to communities is also very low,” says Vijay Ramprasad, researcher at the Centre for Ecology, Development and Research and an author of the studies. “This opens the wider debate of the goal of tree planting, what are we doing this for?”

Some government-funded tree plantations in Himachal Pradesh, India have been successful, including this one established in 1983 . . .

2003

2014

2018

. . . but others, such as this one planted in 1998, have not - in fact average tree canopy cover failed to increase at all across several large plantations in the state, a study found

2010

2017

2022

Google Earth

Martin, the forest ecologist, says she has spoken to farmers in Peru who “had an acre of this planted and an acre of mango planted, an acre of star fruit planted … All these things from years of the Peruvian government coming in and saying, ‘Plant this and you’ll make money.’ And they do, then nobody ever comes to buy it.”

Other projects do appear to contain the ingredients of success. The Albertine Rift is one of the most biodiverse regions in Africa with mountains, deep green forests, savannahs and great lakes spanning 1,000km through six countries including the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda and Uganda. The region is home to the most “endemic” — found in only one place — species of vertebrates on the continent's mainland. Many are endangered.

The Albertine Rift Conservation Society, founded by the Rwandan ecologist Sam Kanyamibwa, aims to integrate biodiversity with farming practices, with a large focus on agroforestry. The charity, which takes funding from government aid agencies, NGOs and private companies, prioritises securing farmers’ long-term buy-in.

It recruits villagers into groups of 30 households and maintains dialogues with each about the impacts on them of local environmental problems. “Our approach is to emphasise the grassroots foundation for change,” Kanyamibwa says, adding that helping villagers make the schemes profitable is a key focus. “We talk to them about financial planning, identifying the markets, the products, the packaging. It is a business.”

Farmers are supported to maintain the trees long-term via villager-managed microfinance funds. The charity visits every project twice a year, the oldest of which is 10 years old, and “never stops monitoring” them. It prioritises biodiversity by distributing 25 species to each project, including native, non-utilitarian trees and shrubs alongside those that provide fruits and nuts.

The charity says it has observed “more insectivorous bird species, butterflies and bees using agroforestry farms as habitat”, although it does not collect data. Kanyamibwa says each family’s profits have, on average, risen from $50 a season before Arcos’s interventions to $300 a season, adding that the charity has now worked with 40,000 families.

The dozens of 1t.org corporate pledges feature planting for both agroforestry and non-productive, wilder woodlands. For the latter, allowing trees and shrubs to naturally regenerate is seen as engendering the most biodiverse and resilient ecosystem. Many of the pledges do mention “assisted regeneration” as well as active “afforestation”, but 31 of the companies still pledge to actively plant specific numbers of trees.

Some argue this is at best an expensive distraction and at worst an active harm to the projects’ biodiversity and resilience. “It sounds great to a donor to say you funded us planting a million trees. It sounds less good to say, ‘You funded us with this huge area to go in and selectively weed to ensure the native species are not being overwhelmed,’” says Martin.

The attention lavished on actively planting trees is misplaced, she suggests. “Forests do just grow on their own.”

Visual storytelling team: Dan Clark, Liz Faunce, Alexandra Heal, Sam Joiner, Kripa Pancholi-Patel, Alan Smith, Irene de la Torre Arenas and Justine Williams. Additional design by Caroline Nevitt.

Notes and sources

Additional experts consulted: Susan Cook-Patton, The Nature Conservancy; Eric Coleman, Florida State University.

Geospatial data for satellite imagery of Indian plantations provided by Anthony M Filippi, Burak Güneralp, Brendan Lawrence and Andong Ma of Texas A&M University and Vijay Ramprasad of the Centre for Ecology Development and Research, Dehradun.

Geospatial data for mapping of Irish timber plantations provided by Neil Foulkes.