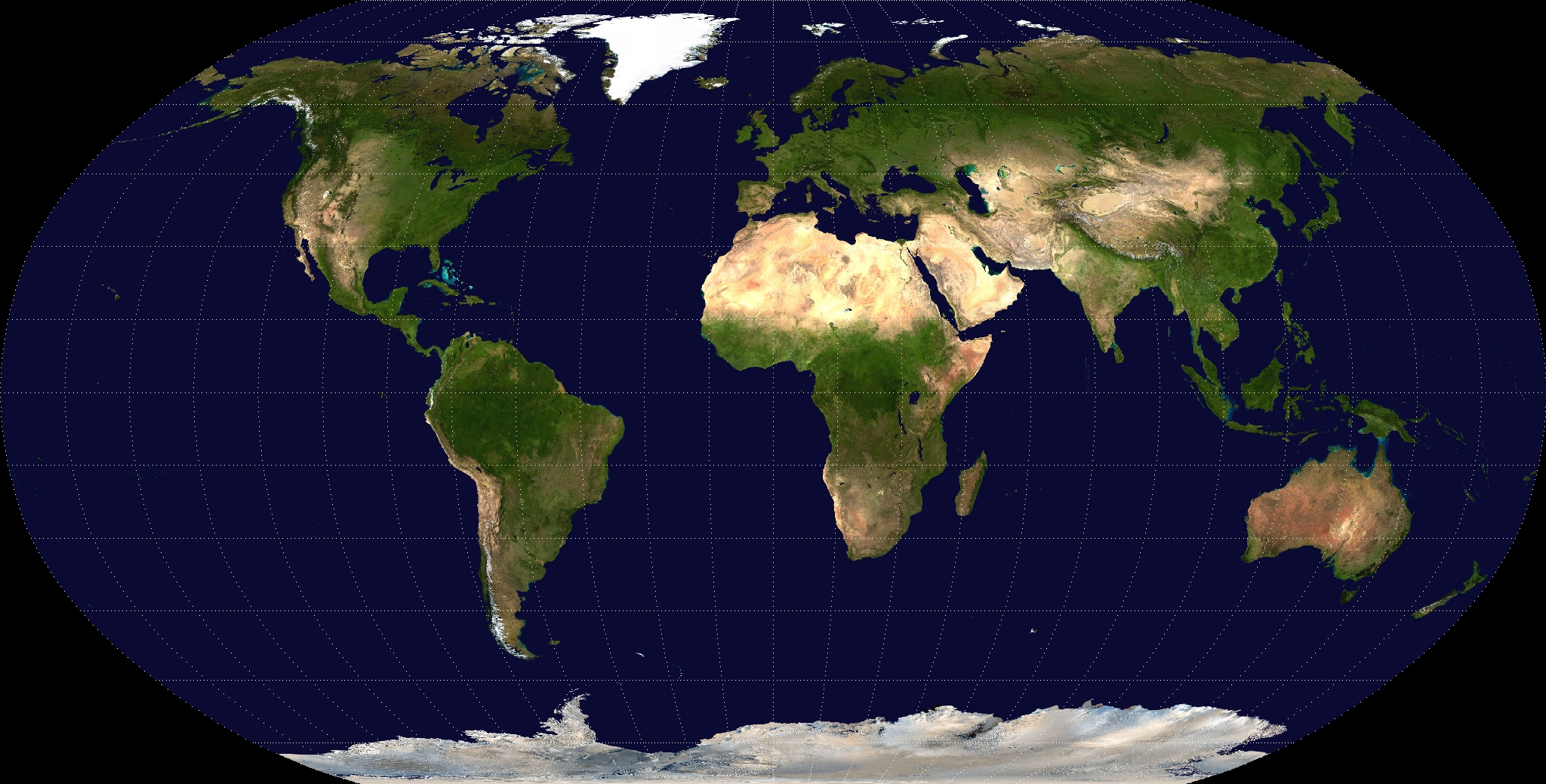

Democracy, according to many observers, is now in the hands of a small band of voters in a half-dozen swing states, whose feelings about Donald Trump will determine whether it endures or falls. From that perspective, all the other voting across the country this year, beginning with the Iowa caucuses, next week, is merely a gruelling prelude to the tense wait, on November 5th, for results from Maricopa County and the Philadelphia suburbs. Much does depend on those voters. But democracy’s struggles will play out on a far vaster field. Thanks to an alignment of calendars, 2024 will set a record for the greatest number of people living in countries that are holding nationwide elections: more than four billion, or just over half of humanity. Even more depends on them...

This year is about voting, in all its hazardous glory. There are different ways of counting, but The Economist has tallied seventy-six countries where the whole eligible population has the chance to vote, even if, as in Brazil, it’s only for local offices. (That election, in October, should serve as a midterm assessment of President Luis Inácio Lula da Silva.) The countries involved—from Algeria to Iceland, Indonesia, and Venezuela—are startlingly varied, including in their commitment to actual democracy. The Economist rated forty-three of the elections as free and fair, with flaws even in the freest, ours among them. One of The Economist’s tests is whether an election has the capacity to bring about real change, in terms of policy and who is in power. Put another way, the stability of democracies depends on the capacity of elections to be destabilizing. An election that doesn’t involve some risk, to someone, is hardly any good.

Those risks should be about outcomes and not, of course, about the dangers of voting or of running in the first place. Bangladesh gets the election year started on January 7th, after a bitter campaign in which the opposition complained of politicized arrests and called for a boycott of the vote. But democracy is, in a number of respects, in an even more perilous state in Russia, where Vladimir Putin will almost certainly be re-anointed in an election in March; the man who might have been his most potent challenger, Alexei Navalny, is currently an inmate at a penal colony in Kharp, in Western Siberia. Still, the turnout of Russian voters, and the mood on the street, will reveal something about Putin’s hold on power. (Iran, where elections are contested among a very limited spectrum of candidates, will face a parallel test that same month, following a year of mass protests.) Meanwhile, Ukraine’s President, Volodymyr Zelensky, has said that he doesn’t intend for an election scheduled for March to take place, because, given the war, it would be “absolutely irresponsible to throw the topic of elections into society in a lighthearted and playful way.” That choice may be comprehensible. Yet it still feels like a loss, and possibly a tragedy.

The single largest election this year, spanning April and May, will be for India’s Lok Sabha, the lower house of parliament, whose five hundred and forty-three members represent 1.4 billion people. The sprawling campaign will determine whether Narendra Modi remains Prime Minister (it would be a shock if he didn’t) and if his Bharatiya Janata Party will be forced to form a coalition (possible). This election will closely follow one in Pakistan, which has been shaped by the criminal conviction and imprisonment of the opposition leader, former Prime Minister Imran Khan. Pakistan may also offer a harbinger of the rise of artificial intelligence in elections: Khan, who has been blocked from making campaign and broadcast appearances, released a video with A.I.-generated audio of himself giving a speech.

The second-largest election will be for the parliament of a polity that is still, in many ways, being formed: the European Union. That election will be held in June, across twenty-seven countries. Members of the European Parliament caucus not by country but by transnational meta-party—both France’s Renaissance and Germany’s Free Democrats are part of the Renew Europe group, for example. The election will help to set Europe’s priorities, notably with regard to Ukraine. It will also be a barometer of the political moods of European nations, many of which are regarded as restless; right-wing populists won a surprise victory in the Netherlands last year. (In the United Kingdom, which left the E.U., Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has until January, 2025, to call new elections.)

In North America, Mexico will choose a successor to President Andrés Manuel López Obrador in June; the leading candidates are two women, Claudia Sheinbaum and Xochitl Gálvez. Not counting the E.U.’s joint poll, however, the continent with the most elections in 2024 is Africa—eighteen by The Economist’s tally—though some have yet to be scheduled. One of the more closely watched will be in South Africa, where the African National Congress has a significant chance of losing power for the first time in thirty years, largely because voters view its leaders as corrupt. In South Sudan, where an election that was originally scheduled for 2015 is supposed to take place in December, the question is whether people will get to vote for anybody at all.

Meanwhile, an unusual number of Chinese observation balloons have been spotted over Taiwan, which is in the midst of a three-way race for a new President, to be decided on January 13th. In case anyone missed the message, one Chinese official said, according to Reuters, that people in what he called “the Taiwan region” ought to “make a correct choice,” and suggested that the wrong choice could lead to war. Lai Ching-te, of Taiwan’s governing Democratic Progressive Party, is seen as less conciliatory toward China than Hou You-ih, of the Kuomintang. The polls are very close.

The obvious question is: Of these dozens of elections, which is the most important? We might be inclined to say that ours is, because we are the United States, and because of all that Trump might do. But we don’t know what crises and triumphs will result from elections elsewhere, or what going to the polls might mean for another nation’s rise, even as we contemplate where our country is in the arc of its world significance. We don’t know what the effect will be—demoralizing, unsettling, or inspiring—of month after month of election news. Most of all, in a good many places, we don’t know who is going to win. ♦

Published in the print edition of January 15, 2024, with the headline “The Big Vote.”